Open Book

In Cuba journals were deadly. Keeping one meant risking your life if the local party leaders decided to conduct an unannounced search of your house. Even without a search, spying neighbors were a threat and being seen writing raised many suspicions. It was best not to express.

In Cuba journals were deadly. Keeping one meant risking your life if the local party leaders decided to conduct an unannounced search of your house. Even without a search, spying neighbors were a threat and being seen writing raised many suspicions. It was best not to express.Mama had a hard time with my journals. Even though we were in America, not Cuba, she had nothing but contempt for me when I started writing out my thoughts and feelings. It could fall into the wrong hands; you don’t know who might end up with it one day; it could ruin your life. Her warnings didn’t make me tremble so much as laugh. Devastated-teen poetry and plays encoded with sexual innuendo filled my high school journal, as did rants about Shanika’s honesty and Jenny’s superficiality and Kevin’s onion breath.

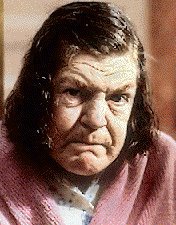

After I came out, and dad removed the door to my room and the phone from my wall, and both of them listened in on all my telephone conversations because I wasn’t allowed to speak to any males, and after she began following me in her car when I went jogging lest I detour into some man’s bedroom, Mama became more involved in my journal. She called me into the kitchen one Saturday afternoon. In her hand she held it. To her right, on the shiny blue kitchen counter, a Spanish-English dictionary, which she was never able to use well. She demanded, with a sweet tone and a smile on her face, that I translate, out loud, certain entries for her. Ever the obedient one, I did. To resist would have raised suspicions that I wasn’t working with Christ to change my ways as I’d promised mama in exchange for her ceasing to perform nightly exorcisms against the devil of homosexuality that she was sure had taken my soul. “I’m the only person you can ever trust because no one will ever love you as much as I love you,” mama said to me, almost daily, and most certainly anytime she wanted me to share my innermost self. To refuse sharing meant I had something to hide. “Honest people tell their mothers all because they have no dirty secrets.”

Mama wasn’t pleased with my writing. “You can never write about other people. Never write down what you think about other people—you don’t know if one day those people will have power over you and then what? You’ll find yourself in the muck.” She was the only muck I was in.

The metaphors in my poetry and plays became thicker, impenetrable enough to guard their truths from mama’s vigilance. Except they failed. “I know you’ve been writing things about me in codes. I know it’s me. That character in your play is me,” she accused in a later confrontation. She was right. I was writing about her. It was all spiders and webs and snakes coiling and crazy old women chasing innocent men with their dirty brooms. She recognized herself clearly in my mirrors and I hated her for it.

It was war. I hid hateful little mines inside my entries, meant to blow her heart: “Mom, if you’re reading this it’s because I loathe you and you’re a terrible mother.” Of course she’d find my embedded bile, and she’d confront me, and I’d tell her she had to stop, and she wouldn’t. So I stopped. I stopped writing. Because eventually I wanted a phone, and to be allowed to have friends again. I held on to every bit of feeling, and when I felt I would explode, that’s when I stole one of dad’s disposable razors and learned to cut my arms. Finally alive. My blood, freed, my only ink.

1 Comments:

this made me cried, alex.

2:33 PM

Post a Comment

<< Home